By Michelle Martinez

Winter 2011 Kaplan Award Winner

Part One

“Why did he do that?” I asked Peter through a sob. My words triggered something deeper in me: the helplessness of the unanswerable question: Why is this happening to me? And I started to cry briefly, but the tears felt so far away and alien, just like the moment I was living in its baffling reality did. I felt Peter’s warm hand squeeze mine where he’d been holding it for the past twenty minutes or so and it grounded me a little.

“I don’t know, sweetie. I don’t know. Only God knows.”

God can’t comfort me, though, I thought dismissively before I looked up at the stars, trembling, and mentally cried out for my mother over and over again, willing her to hear me from 12,000 miles away. I suddenly thought of the other driver.

“What happened to him? Is he…?” I looked down from the wordless stars again and into Peter’s face.

“Oh…You don’t want to—” The man named Peter, who made me think of the Biblical Peter in those moments while he acted like my savior, seemed to hesitate, not knowing if he should answer me honestly or not. “He didn’t make it, hun.”

“Oh, God.”

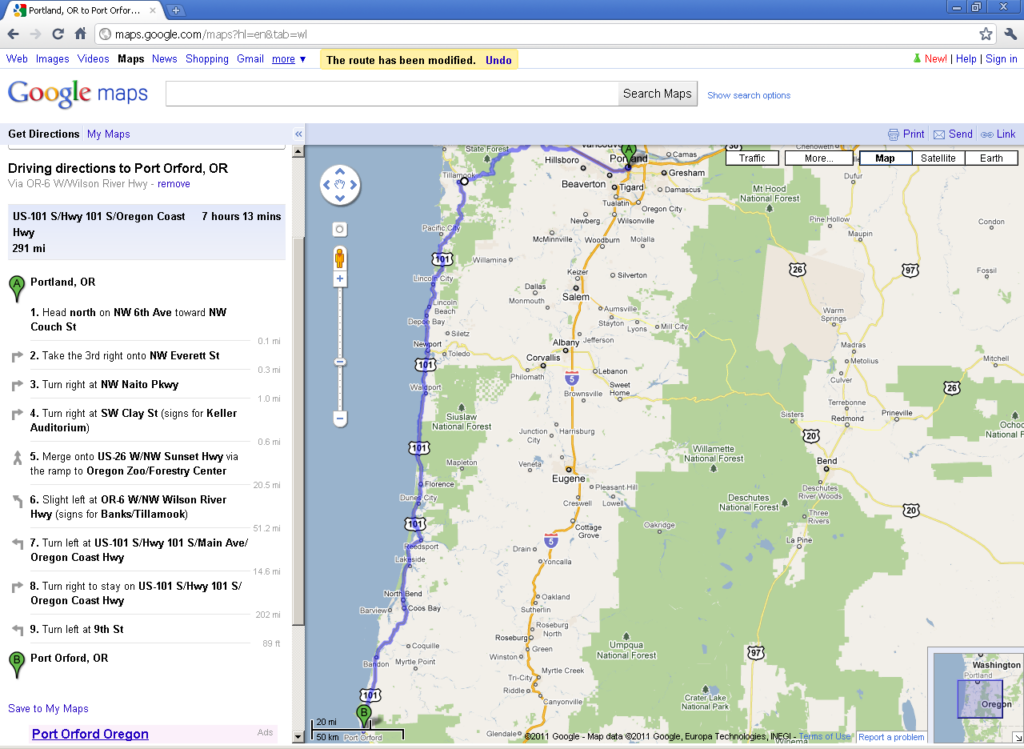

Run a search on “oregon highway 101 accidents” in your favorite Internet search engine and you will see a plethora of news stories within the past few years of strange and horrifying, and often fatal, car accidents which have transpired on the scenic Oregon coastal highway. One could almost surmise that they happen like clockwork. They are expected. It is not uncommon to see those—what have become almost ubiquitous—white crosses along the side of the road while taking this route.

But what is the toll this type of frequent trauma takes on the communities surrounding Highway 101 in Oregon? Often, the people hurt or killed in these accidents are outsiders, tourists—not necessarily from out of state or all that far away, but outsiders nonetheless. Of course, from time to time, a local is victim of one of these inevitable car accidents.

Recently, I spoke with an attorney named Jeff Waarvick located in Newport, Oregon about this very issue. I wanted to do this because I felt it would be something of a means of connection of some sort because my story had weaved its way into the larger story of the people in towns much like the one where my accident took place. What Jeff told me was that these accidents affect everyone in the community. This of course is especially true when the accidents involve local people, but even if the people involved are tourists or people passing through, as was the case with my accident, the devastation is still felt in a shock wave throughout the community. The news travels fast of every new accident which occurs, support is given, and the healthy caution towards Highway 101 that these people feel is reinforced.

Jeff’s information corroborates my own experience as after my accident, even the staff at the Motel 6, a national chain, which my grandmother stayed at while I was in the hospital in Coos Bay, Oregon (not even one of the smallest towns on the coast) had heard about the accident and so treated her with the kind of compassion that you really only see in close-knit communities. They allowed her extra amenities and once I was released from the hospital, gave her, for free, several pillows from their rooms so that she could cushion my broken leg as I was transported in the back seat of her car back to my apartment in Portland.

Highway 101, Jeff told me, is somewhat feared by these small communities it bisects. Parents often don’t want their children of driving age to use the highway, nor do they feel that it is safe for pedestrians to try to cross the large and heavily used highway. If families live on the east side of the highway and want to get to the ocean, they have to cross the dangerous highway, and this is often when accidents happen.

While the highway widens out from two lanes into four in most of the cities it cuts through, and the speed limits drop down to 35 or lower, a lot of the tourists or passers through do not adhere to these speed limits. The highway is dangerous no matter where you are on it, in a car or not.

“The smaller the town, the bigger the crater if something like a bad car wreck happens. In a town of 3,000 people, if two people die, everyone feels it,” Jeff said. “Especially if they are kids. Highway 101 is like a flat wall that divides these towns.”

Jeff also related a story to me of his personal experience with deadly car accidents on Highway 101. In 1974, when he was an intern at the District Attorney’s office in Newport, he got a call from the Chief Deputy District Attorney asking if he wanted to go on a blood run with him. Jeff had no idea what a blood run was, but agreed to go along. Once with the other man, Jeff found that they were heading to the hospital. Immediately upon entering the building, Jeff saw that everyone in the lobby was solemn. There was an air of urgency. There was blood on the floor that was being cleaned up. A hospital chaplain was on the phone making a call.

It turned out that there had been a very bad car accident involving a logging truck in which a young man had already been pronounced dead. The chaplain was calling the kid’s father. The young man had been the passenger to a girl who had been driving the car with her new learner’s permit. The girl was in the operating room, in critical condition, and in desperate need of blood, but the blood had run out.

Immediately, Jeff and the other man were asked to give blood while another person had already gone to make the actual “blood run” to another area hospital to see what blood supplies could be taken from them. He spent the next hour giving blood, but the girl did not make it.

There are hundreds and hundreds of stories just like this throughout the history of the highway. Mine is just one of them.

A2 — THE WORLD, Coos Bay, Ore. — Monday, August 30, 2004

Man killed in accident south of Langlois Friday night

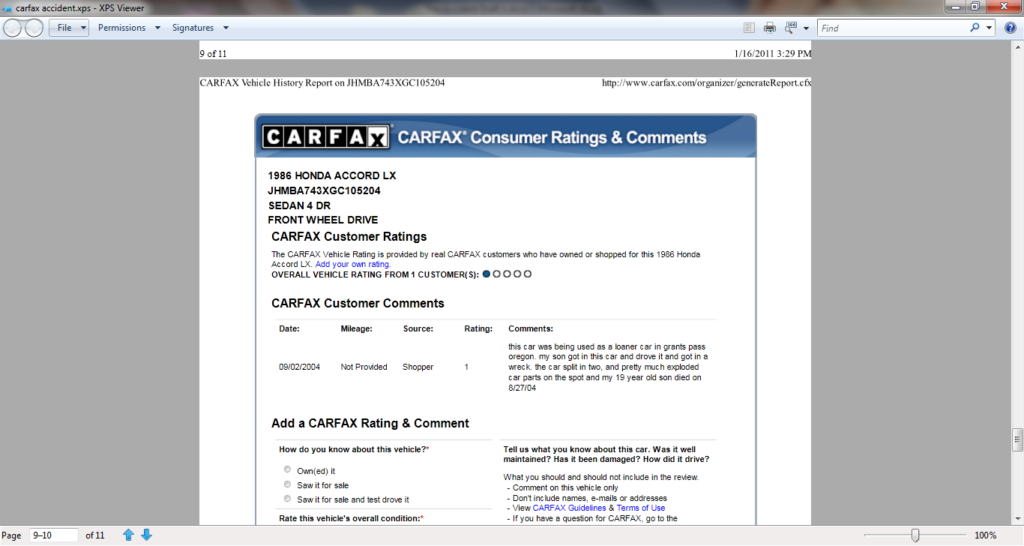

A three-car wreck 8 p.m. Friday on U.S. Highway 101 ended in one death and two others being sent to Bay Area Hospital with what police said were serious injuries.Police said Michael Gomez, 19, of Brookings, was pronounced dead at the scene after his 1986 Honda sedan, traveling northbound, collided with a southbound 1992 Subaru sedan after Gomez crossed the center line.The Honda was cut in half and one of the pieces struck another southbound vehicle, a 2004 Jeep driven by Kim Phillips, 46, of Roseburg.

The driver of the Subaru, Michelle Martinez, 22, of Portland, was listed in fair condition Monday morning. The hospital had no record of the passenger Allison Smith, 22, also of Portland.Phillips was not injured in the wreck.Traffic was stopped in both directions just south of Langlois, for more than two hours, according to Trooper David Wehner.Bandon Police, Lanlois Fire Department, Sixes Fire Department, the Oregon Department of Transportation, Bay Area Ambulance and the Oregon State Police responded to the incident.

OSP and the Gold Beach Patrol Office are investigating the incident.

In reading this, I wonder about the literal intersection of my life with that of Michael Gomez. I look at the newspaper article above and think about other such articles I have read—articles that were not my story. The details are often so sparse in these articles, so impersonal, that one struggles to find something to connect with in the words. Words represent lives, and even if they are in print in a newspaper, they are no more revealing or tangible than the electronic words you read on the Internet.

As a reader, you try to imagine, with the skeletons you are given, the fleshed out bodies of the human-beings behind the headlines. Who are these people who actually lived these newsworthy experiences? How are they connected to one another? I often find myself wondering these particular questions about my newspaper article.

My headline.

Although, in fairness, the headline wasn’t really mine. I was just part of the story—and yet, I know nothing more about the young man whose headline it really was than any other person who, waking up at 7 in the morning, grabs the newspaper from their front porch to read the article and shake their head in dismay. I know my experience of it, but what about his? Who was he? Who loved him and who mourned for him? We altered the course of each other’s lives in such a drastic way, and I go on to tell the story and he does not. We have one, solid line of connection, but what kind of connection is it?

Human beings all long for connection. We seek it out in each other, in animals, in nature, and in our spiritual beliefs. We search for connections in order to find meaning in our lives and most importantly, in our deaths. Death is a terrifying specter for many of us. Especially for those of us like myself who don’t have religious beliefs to reassure ourselves with. I often have moments of panic when I think about my own death, about the possibility of nothingness afterwards. This is perhaps part of why I think so much of Michael Gomez and my own brush with death. And also why I think about the other deaths I have experienced. Additionally, it is perhaps why I long to connect deeply with everything and everyone I possibly can so I can escape the isolated space inside my own head trapped with its own fears of annihilation.

Moments of connection happen both randomly and deliberately. In today’s modern world, however, it has become increasingly difficult to make these connections, despite (or perhaps because of) the advent of technology that should aid, not hinder these connections. Words, not spoken, but written, have become one of our biggest means of communication. We text message, we e-mail, we post blogs, and then finally, we read. We read endlessly the electronically represented concepts and ideas of other people who may be down the block from us, or across the world—people whom we know and people whom we don’t know.

Some of us are better at connecting than others. As a child, I was always shy, inhibited, and while not friendless, definitely felt an inability to share connections with people who weren’t “like me”—nerdy and feeling socially outside the rest of people “our” age. Of course, these feelings have lessened since I’ve grown older and realize we’re all struggling with these very same feelings a lot of the time, but at age 14, it led me to drop out of high school when I was given my first computer and was able to explore an entirely different world where I did feel I could be outgoing and make new connections all the time. I led my life predominantly online, even by the time I was back in school going to college at age 21. By then, however, I was starting to learn that nothing really compares to real human contact— that hand holding yours in the dark, keeping you tethered to this world when you feel yourself starting to slip.

Can there be a connection in death?

Death is something I’ve struggled with understanding and accepting for a long time, probably since I was a child. For me, having always had a little trouble fully connecting with people, I found that I fully and very deeply connected with animals. So it was that when animals died, I was far more horrified than perhaps I would have been had a human died.

Then again, I didn’t experience first-hand any human death until I was in that accident at age 22. I do recall at around age 9, my father receiving a phone call from his family in Venezuela about the death of my Godmother, Dianora, who had been killed in a car accident (also at the age of 22) due to a drunk driver running a stop light. Because I didn’t know her all that well, I did not feel the loss the way my father did, but I remember him screaming and crying. I had never seen him so emotional, even during his frequently loud fights with my mother.

But my more direct experiences with death started with animals (as maybe is true for a lot of us). I don’t remember losing my first pet fish, but I do remember the agony of losing my first pet finch. While I was growing up in Flagstaff, Arizona, I had come home from playing at my childhood best friend Rachael’s apartment to find him upside-down on the floor of his cage—suddenly dead. He hadn’t displayed signs of illness prior to that. It was only much later that I understood that small birds, and many other prey animals, don’t display signs of distress so that they are less likely to be picked off by those that hunt them.

I had taken his small body from the cage, crooning his name at him sadly: “Jolie, Jolie…” And then I took him with me outside to the large pedestrian and bicycle thoroughfare that stretched by just 20 feet from the front door of our small abode in the Northern Arizona University campus family housing section. I sat with Jolie, cradling his body in my hands as I cried quietly in the evening sun (I had thought the bird was male when I got him, just because that was what I wanted him to be, but then found out she was actually female because she laid eggs—something that had been traumatic for me and made me cry in dismay before my mother told me I could simply keep thinking of her as a him in my head and no one would know anyway).

Some students passing by told me I had a pretty bird and I didn’t know what to say except to shout after them that, “He’s deeeaaaaaad!”

My mom didn’t know what we should do with his body and I didn’t want to bury him because I knew we wouldn’t be in this place forever. I didn’t want to move away and leave his remains in a yard that uncaring people might take over. So, we wrapped him in a paper towel and put him in a Ziploc bag and froze him. Eventually, that freezer filled with more birds and eventually hamsters too. I couldn’t bear the thought of burying my babies and letting their bodies decompose. It felt so disrespectful. The fish made their way in there after death as well, but only the really special ones. Most of the other dead fish got eaten by their tank-mates.

As I got older, I finally became psychologically ready to start burying the bodies of my little pets, but losing them was always still so hard. It never seemed that any of them died of old age, really, but of some malady instead. Particularly traumatic, was the death of my oldest parakeet named Beau. He and Jolie had been good friends, but the original Jolie died much earlier than Beau (I had a few “Jolies” before I got one that wasn’t sick and which outlived all the other birds—this came after I learned to never buy pets from Wal-Mart again).

Eventually, I had four birds—two finches and two parakeets. I didn’t know their actual sexes, but I made them male and female pairs in my head although they all had separate cages. I would hold open the cage doors with twisty ties between the two finch cages and let them hop back and forth with each other frequently and noted with glee that they snuggled together in their little nests which of course they both laid fruitless eggs in. The pairings were like this: the male parakeet was Beau and the female parakeet was Belle while the male finch was Jolie and the female finch was Joliette (a name I made up).

I had different character voices which I made for each of them to express how I thought they were feeling. Beau’s voice was a very low voice and he was always saying, “Get away!” because he hated anyone near his cage and would run and hide. Belle also said “Get away” but she was more feminine about it and had a very fluttery light voice because she was always singing like that (I had to try to mimic her singing). Jolie and Joliette just had standard baby-voices, one pitched a little higher than the other to denote her femaleness.

At any rate, they were very, very special to me, and then Belle started acting strange. She would randomly fall off her perch and then scuttle around the floor of her cage without being able to figure out how to get back up. She died that same day—I remember that I didn’t go to get my cheerleading pictures taken that day so I didn’t appear in the team photograph. I was 13. A few weeks after that Beau started exhibiting the same behavior and so I immediately told my mom we needed to take him to the vet. They gave us an antibiotic for him but they said it didn’t look good for him. This was when I found out that the birds hide their illnesses until they are very advanced. I also found out that it is very hard to treat small birds like Beau because their hearts beat so fast that if they get too upset, the hearts just stop.

Beau survived the trip to the vet and seemed a little perked up when we got home, so I almost didn’t want to give him his medication the next day, but I also didn’t want to assume that he would continue to get better. I was still hurting over the loss of Belle, so I asked my mom to help me administer the syringe full of pink liquid to him.

It didn’t go well. It didn’t go well at all.

While I was holding him, he struggled hard, and my mother squirted the antibiotic into his mouth, but it started to come out of his nose and he became more upset and then I felt his struggles weakening and then he abruptly lay still—pink goo dribbling from the nostrils above his beak. I felt directly responsible for his death. It was a nightmare.

It took me a long time to recover from my horror. I wrote a strange prose-poem type thing after his death that was extremely over-dramatic and dark, but which did capture my devastation at the time.

I didn’t deal with a significantly traumatic death like this again until my car accident on August 27th, 2004.

August 26, 2004.

Evening. Grants Pass, Oregon.

“We should go up to Eugene and hang out with Mark this weekend,” Josh said, looking up from the computer screen he’d been reading. “It’s his birthday on Sunday and he’s having a party in the woods. Camping. There’s a hog show this weekend too. I wanna take my bike. We could leave Friday afternoon, yanno?”

His sister, Lily, shrugged her shoulders from where she sat on the sofa, flipping through the TV channels. “I’ve gotta work this weekend, but I bet Mike will wanna go. He likes that kind of stuff, and he and Mark met at Sarah’s party a few months ago, remember?”

Mike was a guy Lily had been seeing on and off again for the past couple of months. She knew Mike had moved to Oregon from California to live with his dad and step-mom. He’d become Josh’s best friend almost immediately upon their meeting. The two were years apart in age, Josh now 25 and Mike 19, but the pair was almost closer than Mike was to Lily.

“Yeah, but he’s not gonna get up there without you….Unless you let him borrow your car?” Josh raised his brows at his sister and gave her a puppy-dog look.

Lily rolled her eyes. “My car’s in the shop right now, remember? I’ve just got that crappy Honda they gave me.”

“Oh. Right.” Josh huffed and went back to reading MySpace. After several moments, he looked over at his sister again. “Wait, couldn’t he just drive the Honda?”

Lily put down the remote and lit up a cigarette. “Yeah, I guess, but then how am I going to get to work?”

“Ask Sarah?”

“What do I get out of it? I get no car and no boyfriend for the weekend.”

“Uh… How… about…”

“How about you take mom to the airport next week instead of me?” Lily grinned at Josh.

Joshua snorted, but then conceded with a nod.

“Deal.”

August 26, 2004.

Afternoon. Portland, Oregon.

“I really need a vacation. School has been hell lately. We should go somewhere this weekend. Don’t you have Fridays off too?” Allison asked as we drove around the sharp corner to her apartment complex in Multinomah Villge.

“Yeah,” I replied. I turned down the music and slowed the car as traffic built up in the popular Portland neighborhood. “Trouble is: where do we go? I’m spending money I don’t have at this point. Plus, I have to go somewhere that I can take the dogs, you know? I don’t have anyone to watch them on such short notice.” It was Thursday afternoon and I was driving Allison home from class.

As I thought about it more, I gave a little sigh. I was worn by school and life too. Living off of borrowed money, working part-time, and doing homework every free hour of the day was getting to me. Not to mention, I’d been taking a lot of road trips lately, not all for pleasure, and the driving was really starting to wear me out. While I wanted a vacation, I kind of wanted not to have to go anywhere to take it.

“Hmm…Yeah, I’d need to bring Gryffin too. I don’t want Andy taking him. He’s starting to act like he thinks Gryffin is his dog and it’s really bugging me.” Allison and Andy had been living together for the last several months, but were on the verge of breaking up. He was 44 and she was 18. It was no wonder.

I pulled the car into the spot reserved with Allison’s apartment number and parked. She didn’t have a car, so I parked there when I came to visit. I’d met Allison at Portland Community College where we both went to school. We had a slight age difference, I was four years older than she was, but we struck up a friendship.

We weren’t particularly close, we didn’t have a whole lot in common, and of course, there was always my inability to feel deeply connected to most people. It probably didn’t help that she was a little rough around the edges and I was a bit of a straight-laced nerd, but I definitely had taken the road-less-travelled in my life, so I could relate to people who weren’t just living the fast-track to success in America, and in this, we found at least something to relate to one another about. Still, we didn’t talk about ourselves that much. I didn’t know much about her past except that her mother was dead and that Allison had very clearly not been living with her family for quite some time, despite only having turned 18 a few months ago.

“I don’t know where we’d go. Maybe we should just hang out here for the weekend. We could go to a movie or the mall or something.” I offered with a shrug.

“My aunt and uncle have a ranch type thing down in Port Orford. I bet we could visit down there. They have animals there, but they’d probably let us bring the dogs if we kept them tied up or with us all the time. I used to go there when I was kid. I could call them and I’ll let you know tonight?”

Now this piqued my interest. I loved ranches and farms. I very badly wanted one of my own— a fact I talked about with people frequently. The idea of having land to work and animals to tend appealed to something deep inside me. That was the connection I longed to have: a connection to the earth and to my own life. Forget this working in an office stuff where I would earn things for my survival in an abstract, twice-removed sort of way. I wanted to really know what it felt like to have to produce things that I would use first-hand for my continuance.

“That would be so awesome!” I exclaimed a little too eagerly as I watched her get out of the car. “Just text me.”

“Will do! See ya!”

And the car door slammed behind her.

I received her text confirming our trip too late that night to bother packing the car up. It could wait until morning. I texted her back saying that we should take Highway 101 along the coast to get down there as I’d driven it exactly a week ago when my oldest online friend, Maddy, had come out to visit me the most recent time. I knew the road was going to be full of places to stop and sightsee, so we would have to leave early in the morning. The drive would take about 8 hours, I figured.

August 27, 2004

Afternoon. Grants Pass, Oregon.

Michael caught the beer can Josh threw his way. “For the pre-party once we get there!” Josh had shouted as he began to get all his gear onto his bike. Michael grinned and put the can on the passenger seat through the open window of the Honda he was going to be driving.

“I don’t know where the hell I’m going, Josh. So don’t leave me too far behind, okay? Seriously.” Michael said, watching Josh with his saddlebags.

“Don’t worry. We’re going up 101 for most of the way. There won’t be a lot of ways to get lost. It’ll be a nice easy drive and we won’t have to deal with psycho traffic.” Josh was now putting on his black leather jacket and black helmet.

Mike took the cue and went to the driver’s side of the Honda. “I think I need to fill this thing up before we head out.” He commented as he got in.

That earned him a nod and thumbs up from Josh, who now had his sunglasses on and looked like an alien in them.

And so the friends began their journey after a stop at the nearest gas station.

August 27, 2004

Dusk. Approximately 7:30pm. 3.5 miles south of Langlois, Oregon.

Damnit…I told him not to get too far ahead of me, Michael thought as he gritted his teeth and sped up. The road was windy and he wasn’t familiar with it. I wish we’d just have risked taking I-5, he thought.

Josh had taken off on his bike, passing a few slow cars that now Michael was stuck behind. It stressed him out. He took a deep breath and bided his time until the passing lane opened up. Once it did, he zipped past the nuisance cars and pressed onward, speeding to catch up with his friend.

I looked over at Allison, “Well, that was the end of that CD, should we just go without music for the rest of the trip? We should be there in like half an hour or so.” I looked over as a motorcycle sped past in the opposite direction. There hadn’t been much traffic to greet us for most of the day, but that was picking up. “How are the dogs doing?”

“Yeah, why not?” Allison said, referring to the music. She then glanced back at the dogs in the backseat. Kibble was in a kennel on top of the seat, Silver was lying down next to the kennel, and Gryffin was down on the floor behind Allison’s seat. “They’re fine. I think Gryff’s a little stressed though. He’s not used to this. But he’ll be okay.”

Allison grinned at them and then grinned at me, forcing a smile out of me as well.

“Good. Hey, do you think they’ll let me do stuff like milk the cows?” I had been fantasizing about the idyllic Oregon ranch I had created in my mind all day and about my experiencing the types of chores that would need doing. “I really don’t even care if all they want me to do is shovel the cow shit. I just want to do farm stuff, you know? I’m really, really, really stoked!” I laughed.

“Er…well, I don’t know. I think the cows are a little bit weirded out about strangers milking them, but I can ask for you. Who knows. Though I KNOW they’ll let you clean up muck if you really want to. Weirdo.”

We both laughed.

“Do you mind if I read a bit?” She asked after a few moments of silence.

I shrugged, “Sure. I’ll let you know when I need you.”

Allison leaned over to dig around in the bag at her feet.

Up ahead, a silver car came whipping around the sharp curve in the road and crossed into our lane. Suddenly I let my foot off of the accelerator and the car slowed. What in hell was this guy doing? I felt a flash of anger. I hated insane drivers. I quickly assessed the situation, not yet panicking.

There was no shoulder where we were, just a ditch with trees. There was nowhere to go. I had to hope he’d get back into his own lane in time, but it seemed like there was space. The other car kicked up the dirt on the small shoulder on our side of the road and then careened wildly back into its own lane, at what still seemed to be a safe distance ahead of us. Momentarily, I thought the danger was passed, but we were both still moving toward one another at high speeds and suddenly, the silver car fishtailed and spun out so that it came flying at us sideways, straddling the double-yellow line. There was no time to scream. I could only gasp and brake. I remember seeing Allison out of the corner of my eye, glancing up in confusion.

The time passed slowly in my mind, each action fragmented and yet complete: my foot hard on the brake, the sense of futility. Nothing flashed before my eyes, I didn’t even have time to really feel the dread or fear, I was only aware of the ultimate question with its answer breaking in before it was even done being asked: Is this—YES, THIS IS REAL. There’s nowhere to go.

And so my story can go on from there. But Michael’s cannot. I could tell of my harrowing hours pined in my car waiting for rescue—how it felt, what it did to my psyche. I could write about my injuries, the terror of the ER and the drills and the morphine. I could write of the miracles, the years of recovery, both physical and emotional, and the permanent scars in both, the lawyers, the medical bill collectors, the fight for a settlement…but I’ve told those stories dozens of times. I still want to know: what about Michael and what about death? What about my need for human connection?

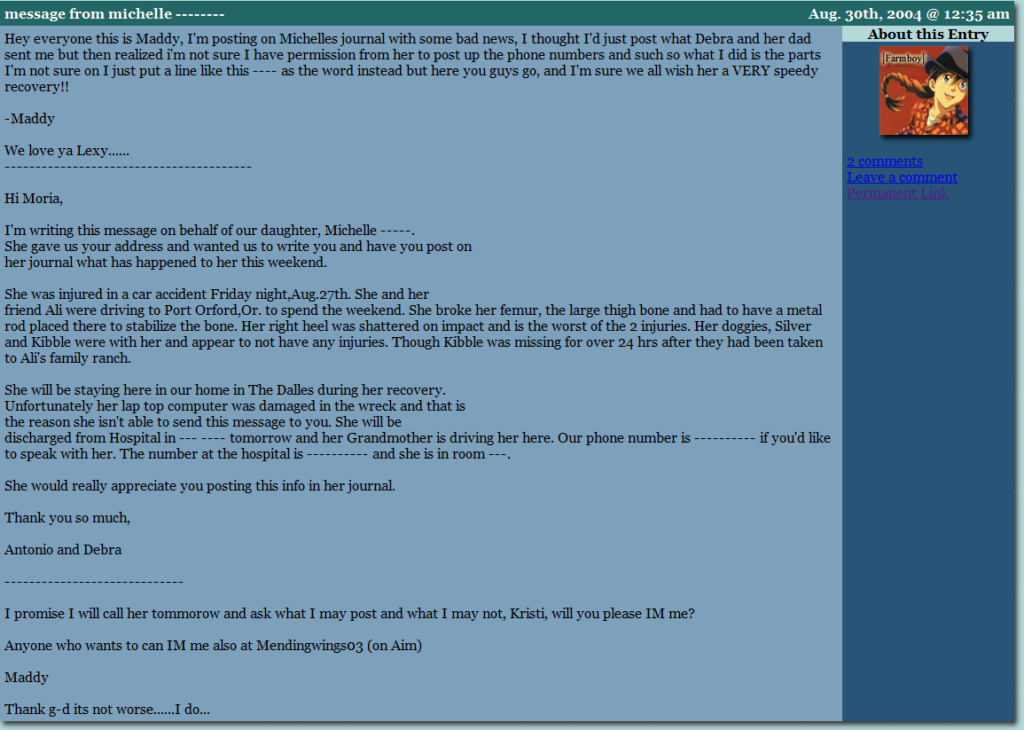

Let me tell you briefly about what happened to Allison and me, because otherwise it’ll be like that item on stage that gets accidentally dropped during a play: the audience can only fixate on that item and not the actual performance until it is picked up or dealt with some way. She and I were extremely lucky. All the beings in our car survived. The dogs had very minor injuries. Allison had a broken collarbone from where her seatbelt saved her life and a large gash across her forehead from part of the dashboard or other vinyl car part from the other car, which had broken through our windshield. I had a femur fracture, a compound fracture of the ankle, and my calcaneous (the heel bone) was shattered—all in my right leg, which had been on the brake pedal.

For years after the accident I struggled with something I’d term survivor’s guilt on some level, and also post-traumatic stress disorder. I feel like I carry Michael Gomez around like a specter at all times. I can easily say the three years after the accident were the worst years of my life despite having had several other very difficult experiences in my time. I was suicidal for those years and terrified of death. I became somewhat obsessed with death and still do tend toward the darker side of things. Then again, I think I was always that way. Maybe that’s why I took this experience to the places I did.

After writing this, I can say that I’ve failed to connect.

I’ve failed to connect with Michael. I’ve failed to really learn anything about him. The scenarios I wrote about him are ones I imagined with the little information I had available told to me through my lawyer during the drawn out procedures that followed for years after the incident.

And now? The years have passed and I have been too afraid to follow the crumbs down the trail toward what was his life. For a time, I thought I would try to contact his mother. I have the information necessary to make contact, to deepen and bring to life (in a sense) the connection we share, but…I’m terrified. Will she blame me for some reason? Will she be bitter? Why would she want to talk to me, of all people? Would my curiosity about Michael’s life be offensive, or healing? Finally, would it be too much for me to handle, positive or negative?

I’ve also failed to connect with Allison. Despite what we went through together, despite my crying out for her when I heard her in the examination room across the hall from me, we have not been in contact for several years. In fact, the elephant in the room when we visited with one another after the accident was so big that it could be said that we really stopped being friends as soon as we had been discharged from the hospital—first her, then me several days after.

I don’t think she blamed me for the accident, but she didn’t remember what happened with any accuracy at all. When she had regained consciousness, she had told the Trooper that we thought we had crashed because I had been trying to pass someone who was going slow despite the fact that there was no passing lane where the wreck had occurred.

In thinking about connections with people—my ability or inability to make them—I see the accident as a microcosm of my life—and maybe not only my particular life, but of all human lives. The connections with strangers who helped on the scene, like Peter or the medics in the ambulance, were fleeting, as have been most people that have come and gone in my life. The connections that could have been, and perhaps were meant to have been more lasting, like with Allison, or even Michael in a different sense, broke apart or never found their footing to start with. I think most people who have lived long enough have experienced this phenomenon.

Sometimes, it seems like we bounce off one another like high-speed atoms, glomming on to certain other atoms for longer periods of time than others before continuing on in our own chaotic little ways, either fused with others or on our own. In the end, all I have of Michael are some written words. I have the accident report. I have the legal documents. But I have no image of him. I have no idea of what he was like.

January 25th, 2011

After re-reading and editing what I wrote, I realized something. In all this talk of technology and the concept of words becoming to be digitally represented more and more frequently, I was suddenly struck with the idea to finally search out Michael on the internet. I had little hope, but felt that I could possibly do some sleuthing and find out more about the young man who has captured my thoughts and imagination for the past six years. The idea paid off.

Of course, I should have realized this sooner, but in this age, everything is online. There were at least 4 memorial websites made for Michael. Among them are many photos and writings from his friends and family. I now feel like I have a better understanding of who he was. All traces of my anger over his recklessness in the accident left upon seeing his picture. I now see his humanity and recognize his ability to make mistakes. He sounded like a decent person, but imperfect like all of us.

Death still occupies a large part of my thoughts rather frequently. I have always liked to watch the true crime shows on television which depict snapshots of real crime victims. I am always struck at how odd clothing looks on a dead body. The minute something dies, all of the inanimate objects on it die too. Clothing stops looking like it belongs and instead looks like it is dressing a tree or a rock or something. It’s strange.

I have also always collected dead animals and saved their skulls or other bones. When I was 5 and my mom took me to Scotland so we could stay a time at a spiritual retreat at the Beshara manor called Chisolm, I remember finding a sheep’s skull out in the pastures and saving it. I painted it with my friends all sorts of different splotches of paint color and brought it home with me to the United States. Years later, as an adult, I had a wallaby skull for a time that my step-father in Australia sent me from a road-kill incident he had encountered. I cherished that thing until a stray dog I rescued ate it.

I still collect dead animal bits. While camping with my dog a couple of summers ago in a field near Winthrop in Eastern Washington, my dog found two large deer pelts that hunters had simply left. Megan, who was with me, and I collected them and took them home. We had them tanned and I feel proud of the accomplishment, although I didn’t kill the poor animal—nor do I think I could ever kill an animal. I have trouble killing spiders in my home. I am transitioning into being a vegetarian for this reason as well. But when things are already dead, they are fascinating and beautiful and I want to have them as a part of a strange collection.

There is a spot in Winthrop which Megan and I regularly “raid” where the bodies of deer hit by cars are all dragged (perhaps by highway patrol). We have collected many interesting bones from that area. I have seal bones from Megan as well; the body of which she had collected after the Marine Wildlife officials had done their bit in removing its head and cataloging its death, leaving the rest of its rotting blubbery body on a beach on Whidbey Island. We bury the dead animals we find which still have flesh on them and dig them out months later as bones. Then we soak the bones in hydrogen peroxide and scrub them clean. I would never want to taxidermy something—that seems disrespectful. Somehow, what I do, feels respectful to me.

Sometimes I feel like I have a special relationship with almost a personified Death, especially since the car accident. It makes no sense, of course, because death is everywhere and happens to everyone, but I feel like I notice it more than a lot of people in our fast-paced culture do. Maybe I deny its existence less, but also suffer more because of that. Who knows.

My next intense experience with death was far more devastating emotionally than any others. My two dogs, Kibble, my adorable female beagle, and Silver, my sweet-faced male keeshond, both of whom survived the car accident with me, were getting quite old. After drawn out illnesses, they passed away 18 days apart from one another. I could not bring myself to euthanize them and I think Silver understood my dilemma because he died an hour before the veterinarian I had called to come to the house to put him to sleep was scheduled to arrive. I think he understood the horrible guilt that would plague me forever if I had to make the final call on when he died or not.

He’d been suffering mitral valve prolapse in his heart for over a year. The first vets I had taken him to had told me to put him down, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I had arranged for his grave at the Oregon Humane Society’s pet cemetery and everything, but then found a local vet who specialized in cardiac disease. He had gotten approval to import a new drug from Canada which helped extend the lives of the dogs receiving it. I immediately got Silver on this medication, and he had his daily routine of pills, but the coughing (due to fluid build-up in his lungs because the blood was sitting too long in one place and the heart couldn’t handle the volume of blood), receded a drastic amount. He lived many more quality months with those medications, expensive as they were.

At that time, I was a 23 year-old full time community college student living alone with two geriatric dogs on medications while struggling to deal with the psychological, legal, and financial repercussions of my car accident. The medications between the two of them totaled nearly $200 a month. My dogs had been with me through thick and thin. They’d been an intense part of my life since I was 12 years old. They had been my only company at home while my mom worked. They stayed with me when my mom moved to Australia to be with her husband 3 weeks after my 18th birthday. They survived the car accident with me. They were like extensions of my being.

In the year 2006, the year of the dog, 12 years after they came into my life in 1994 (also the year of the dog), I lost them both.

Silver had been living with the heart failure for some while, as I already explained, but had many close calls. Finally, he had something else go wrong. He fell down and couldn’t get his back legs to work. He was obviously in pain and seemed to be very distant. I took him to the emergency vet and it turned out that his vertebrae in his back were compressing to the point of him almost being unable to walk. They said they’d give him some cortisone to reduce the swelling, but that was all they could do. The cortisone would also affect his heart and the combination might kill him.

He seemed to recover a little from that, enough to walk in a wobbly sort of way. I took him home, at any rate, but he didn’t really get better. I knew that it was time to say goodbye, but also knew that he didn’t want to go. I could tell. He was the most loyal dog I’d ever seen. He took care of his sister, Kibble, and he took care of me. So, it was my turn to really take care of him in a very profound way.

I nursed him, helping him get up to go outside to empty his bowels and gave him subcutaneous fluids to keep him hydrated. I gave him liquid food and kept him comfortable as he slowly declined. I can’t remember how many days, but it was at least 5 that he hung on, until he was really unable to move entirely. I would flip him over from one side to the other so he wouldn’t get too sore on one side. I cleaned him up when he emptied his bowels on the towel he was on. One night, after giving him his fluids, I noticed that the floor underneath his side was wet. His body was rejecting the fluids. He was going to die very soon.

That was when I made the appointment for a vet to come to the house and put him down the next day. However, Silver had different plans. He knew my agony over making the decision and he had mercy on me. He departed before I had to make the final call. I was lying on the sofa when it happened, I was also recovering from my second surgery on my leg after the car accident so I was staying home with him during all of this and thankfully, my grandmother was also there to help me. He picked a good time for it really, despite the fact that I was recovering from surgery and also in a transitional temporary house in West Linn, Oregon belonging to my friend’s mother. I was staying there for the couple of months before I planned to move to Seattle.

Silver had been lying there relatively motionless, sleeping, and then his breathing changed and he started to whine and cry. He’d done this a couple of times over the days while he’d been in this state, but usually only right before he had to empty his bowels; this time was clearly very different. He started to have some sort of seizure and I got up immediately, alarmed.

“What’s wrong, baby? What’s wrong?” I remember asking him. My grandmother came near. Silver seemed to be struggling against something and I saw his tongue loll out from his mouth and I could tell from its greying color that he was dying. I don’t know why I knew this, but it was instinctive and entirely certain.

“He’s dying.” I said very soberly to my grandmother. I got down next to him and pet him and held him until he was still. Then the heavy wracking sobs came. I remember my grandmother was hovering around me, not sure what to do, trying to comfort me to the best of her ability.

My friend’s mother gave me a nice wooden box that used to be a cabinet for me to put him in when she arrived later that afternoon to see his dead body by the fireplace. She also gave me a blanket to wrap him up in. I put the teddy bear that my step-mother had given me while I was in the hospital recovering from my car accident in there with him to keep him company.

Kibble was not the same after that. She had been showing signs of illness while Silver was in his death process over the days. She spent little time in the room where he was dying. After he died, she sniffed him, and then immediately went into the bedroom and lay down on the bed. I could not get her to come back out to the living room. We took him to be buried at the Oregon Humane Society later that day.

Some people might think that was cruel and I should have put him out of his misery, but it didn’t seem right yet. We don’t do euthanasia for humans (well, we do in Washington and Oregon), but we do it for animals, yet…we can’t communicate with animals on a 100% certain level to know what they wish. All we can do is go with what we think they want. I really felt like I couldn’t make the choice to put him down. I felt and still feel that we all deserve the rite of passage that is death, and actually, the harder it is, sometimes, the easier it is to let go of the world. Maybe this was just for my own sake, but I think he was not in extreme agony and he was not angry with me about it. He left when he was ready to go.

Kibble had not been so deathly ill, she’d had kidney disease/failure for the past three years, but her condition took a sharp turn for the worse when Silver entered his period of dying. I think she realized once Silver was gone that she didn’t want to continue without him. She started fading quickly after that. She also passed naturally in my bed one night. It wasn’t a silent affair. We both knew she had been dying for a week and that it was only a matter of time. She’d stopped eating and I was giving her subcutaneous fluids like I had been giving Silver. She was restless that night and couldn’t get comfortable. I feel guilty now because I snapped at her to lie down and go to sleep because I was very tired and she was keeping me awake with all her shifting. Later that night, I woke up to the strange sound of a jaw opening and closing with near-gasps for air, but clearly no air was going in or out. A long stream of filth squirted out of her bottom. I panicked.

I ran into my roommate’s room, screaming and she told me I needed to get back in there to be with her. I held Kibble in my arms, taking her off of the bed and away from the filth. “Oh, God, baby. Oh, God. I love you. I love you…” And when she was still, I threw my head back and sobbed in a near howl. I had never felt anything so intensely painful. Even while writing this, four years later, I have to control my grief.

Losing the both of them, and especially so close together, was that experience which finally snapped me out of the suicidal doldrums I had been snared in after the car accident, interestingly enough. It had been my complete rock bottom, and I somehow bounced back straight up to the top again. I believe I did this with their spiritual help, but regardless, during the thick of the pain of the loss, it was indeed very horrible. I still miss them and ache for them, and although I have two new dogs now and my family finally feels complete again after 4 years without them, I will always feel their absence to some degree.

After the deaths of Kibble and Silver, I felt the closing of a large chapter of my life. I was out of the worst of the darkness and I was ready to face life head-on.