By Lucinda Roanoke

Fall 2016 Kaplan Award Winner

Lately I can’t seem to stop picking fruit. It seems that everywhere I turn, a tree is reaching out to me, her branches heavy and drooping. She is begging for me to take a load off her, and I oblige. It’s mid-August in Seattle. I’m ready with my bags and boxes. I pick and pick, gleaning after what the birds and bugs have left. I question- why, when so many people are hungry, do I see so much food rotting on the sidewalks?

My harvest fever began this year with blueberries. I drove to a family-owned farm an hour north, and paid 4 dollars a pound to pick fat organic blueberries under the hot sun. I drove away with 5 pounds, but made sure to eat at least one priceless pound while picking. I wasn’t satisfied. Although the blueberries were divine, I wished I hadn’t spent $20 and labored in the heat to get them. However, my appetite for the harvest had been whetted.

One walk around the city grants me the free fruit I’ve been craving. In a vacant lot bearing the omnipresent Notice of Land Use Action sign, I pick enough blackberries to bake a pie. Around the corner, a fig tree has littered the sidewalk with 1,000 fat green figs, their pink insides squashed on the concrete like road-kill. I fill a shoe box. I’ve got a harvest high now and I can’t quit until I’ve found some apples. A few blocks away, my wish is granted. The tree I find is too tall to climb, but there are plenty of bruised apples on the ground. I collect as many as I can, then head home to make applesauce.

Wild gleaning is in my heritage, and it even played a minor role in my conception. My parents met in Spokane, but after a few years, my dad moved to Olympia to attend Evergreen. My mom stayed behind. They wrote letters to each other every week; letters that were saved and then gifted to me when I turned 18. The oldest are from my dad, telling my mom about Olympia. He rhapsodizes about the Sound, the dense forest, and the berries within. “Oh, my dolce! You will love it here. There are so many blackberries!”.

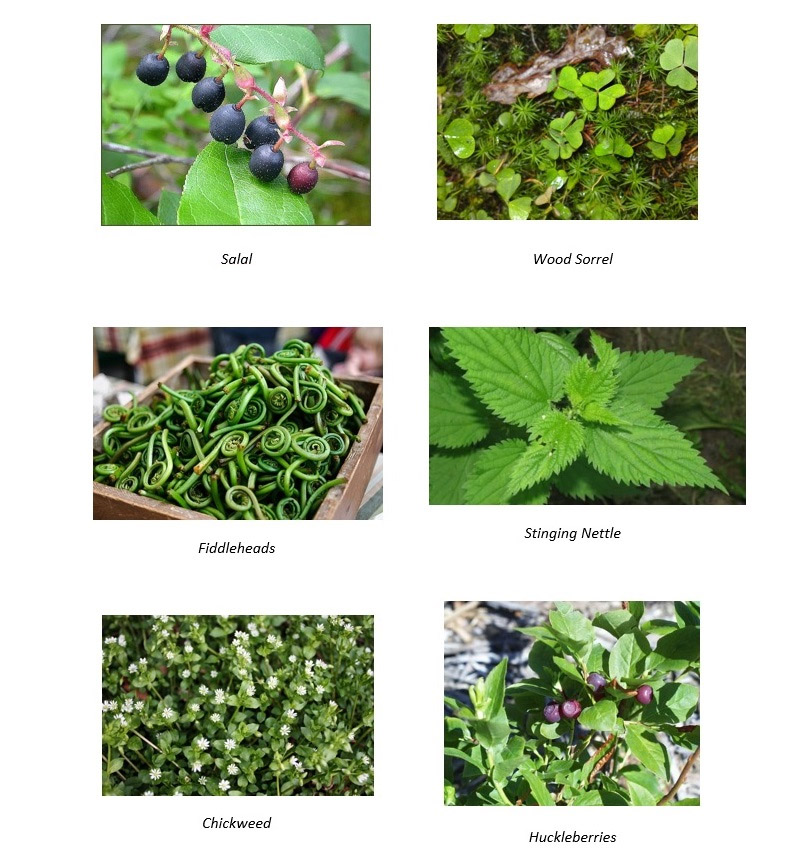

My mom visited, and liked it enough to stay. I like to entertain the idea that the springtime blackberries were what convinced her. She became pregnant with me soon after moving. My dad, a junior in college, would trek into the forest to find fiddleheads for her—an eccentric pregnancy craving. Fiddleheads are a fern’s tender tip that hasn’t yet unfurled. They can be fried in butter, or made into a creamy soup.

I grew up on the edge of the forest, and learned to identify edible berries and plants at the same rate that I learned how to walk. My dad would forage for wild mushrooms that he could sell to gourmet restaurants downtown. I trailed behind him, eating sweet salal berries, chickweed, and sour wood sorrel on my way.

After they divorced, my mom and I lived in a house that boasted a small orchard of three apple trees, two cherry trees, and a small Italian plum tree. But her forage of choice was definitively wild stinging nettles. They grew en masse around the cemetery. She would head out with thick gloves, returning home with a giant bag full of stalks. For more than a week after, nettles decorated our ceiling while they hung to dry.

If I had been born a boy, I would have been named Huckleberry Ray, after my great- grandpa. Grandpa Ray made his living by picking wild huckleberries in the mountains and forest around his home in northeastern Washington. Visiting him always meant having huckleberry pancakes with huckleberry syrup, and a bag of frozen huckleberries to take home.

He would leave early in the morning in his truck, driving deep into the mountains and hills on forest service roads to reach his secret harvest spots. The entire day would be spent in solitude; just him, the berries, and the occasional bear. For the entire picking season, his fingers were stained blue. Like my father, he would sell his harvest to gourmet restaurants in the area. He maintained this lifestyle until his mid-80s, when his memory started to go. The harvest had gotten more and more scarce in those last years, anyway. The bees weren’t pollinating like they used to.

As romantic and whimsical as it is, foraging wasn’t merely a hobby for my family. It was as much about survival and economics as it was about fun. My parents both used the sub-urban bounty surrounding us as a major food source, and my grandfather used it as a primary source of income.

These strategies encompassed a culture and attitude that Olympia especially fostered. I grew up alongside my best friend, whose parents also used foraging and gleaning tactics to feed their household of six. Her father proudly stocked their fridge with unspoiled food from nearby Seattle’s dumpsters; he shot squirrels with a homemade bow and arrow; and he butchered and prepared any fresh road-kill deer he could find. I have sat down to enjoy a vehicular venison stew at their table multiple times.

My family and community passed down their survival skills to me. This knowledge includes gleaning from the trees and vines, but also how to heal my body with cheap herbs and nutritious foods, rather than paying for expensive medications. It includes saving even the smallest amounts of leftovers from restaurants– at this moment I have some bread that was a free appetizer at an Italian restaurant, and in my freezer are the sliced jalapeños that were served beside my bowl of pho soup last week. Living in an urban area doesn’t hinder my harvest. Even if I could afford to go grocery shopping, I wouldn’t want to waste these valuable bits and pieces.

The amount of food that goes to waste in the world baffles me, considering how many people are hungry, even starving. I check certain dumpsters in Seattle on a regular basis. It’s illegal, but I don’t feel right buying raspberries at QFC if I know there are six pristine containers of organic raspberries right out back in their dumpster. And I mean pristine. They throw away produce if they don’t have enough of it to make a nice display. That kind of waste is what should be illegal.

There are a handful of non-profit organizations in Seattle and groups around the world that are devoted to re-routing food waste. Some of my favorites are City Fruit, which organizes volunteers to harvest the fruit that grows on city property in Seattle, and Falling Fruit, an ‘urban harvest’ user-maintained map that includes fertile dumpsters, trees, and free meals all over the world. There are 19,000 map entries for the Seattle area alone.

This isn’t an issue that only low-income people or passionate activists should care about. Everyone should be conscious of the food waste they produce, the food waste they are responsible for, and the waste they are complicit in creating.

I want everyone to know the deep satisfaction that comes with eating a blackberry pie that was made with hand-picked berries from a vacant lot in South Seattle that is doomed to become overpriced condos. I wish everyone could feel the joy and excitement that I do when I see rotting fruit on the ground, knowing that when I look up, I’ll see buckets and buckets of sweet fruit ready for the picking, just above my head.