By Erica Largent

Fall 2014 Kaplan Award Winner

Shana Brent* asked herself if going back home to make yet another attempt at a relationship with her mother would be worth it.

The last time Shana had talked with her mom, had called her on the phone to try mending the brokenness that lay between them, the voice of the woman that had raised her said to stay out, away from her and away from the family with which Shana had grown up.

She recalled her mother’s perennial drunkenness, the screaming matches that came too often. Just within the last year, as Shana struggled through her senior classes and finally graduated high school, her mom had kicked her out three times. Things had been tense since their move back to Washington, but once her mom had learned about Shana’s bisexuality, the aggression had escalated. Maybe it was too late to try to return to her mother again.

But Shana couldn’t think of anyone else to take her in. She had already burned too many bridges staying at her friends’ homes, and the last attempt at living with a boyfriend had not ended well. Her options were scarce.

And so, the 19-year-old bought a bus ticket from Federal Way to Seattle, knowing full well that once she got to the big city she would have nowhere to go. She would, officially, be homeless. Yet, exhausted of fights and closed doors, to Shana this sounded perfect.

***

Cold nights. Rainy weather. Day after day after day of little food, little safety, and little support from most people passing by on the sidewalk. Overcrowded shelters teeming with others also searching for a hot shower and a bed for the night. Difficulty getting a job. Difficulty finding affordable housing. Difficulty starting a more comfortable, roof-protected existence.

The lives that the homeless men and women in our city lead are harsh, dangerous, and often tough to escape. People can grow old on the streets, spending year after year in our Pacific Northwest elements and their own uncertain future. Newcomers to existence without regular housing have to quickly learn how to survive.

The annual tally conducted by the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness this past January reached 9,294 homeless individuals in our county, a number that has been increasing throughout the past decade. In terms of youth, a conservative estimate of 5,000 experience homelessness in our county at some point each year.

Occasionally a child or teenager’s lack of housing can be credited to economics. Since the national recession hit in 2008, the number of school-aged children in our state on the streets has increased by 47 percent.

However, much of the time the young person’s family dynamics play an integral role in their early-age eviction. Rowena Harper, the Executive Director of Street Youth Ministries (SYM) in Seattle’s University District, attributes most of the cases she handles to hostile home lives.

“The large majority of the youth that we see have come from the experience of some kind of break-down in the family that has not allowed them to have a family structure that creates stability for them,” she says.

Harper has worked with 600 to 900 individual youth annually since she first started with SYM a decade ago. Slender and petite, well-groomed and well-dressed, her near-constant smile and warm eyes make one feel immediately at ease. They serve her well whether she is encouraging the youth that visit her office seeking help or strolling up and down University Way in the cold, handing out granola bars. Time and time again, the stories she hears recount unhappy homes and poisonous relationships with loved ones.

“Their parents could have had a mental illness, or been abusive, neglectful,” she explains, “or the child has had some kind of mental illness which the parent decides they can’t deal with anymore.”

This is especially true for children in the foster care system. Sometimes a family decides that a foster child just doesn’t work with their lives. In other cases, those leaving the system on the cusp of adulthood are not always prepared for what lies ahead: about a third of King County foster children turning 18 become homeless.

Those that identify as part of the LGBTQ community also face a life on the streets more often, making up 22% of the homeless youth and young adults in our county.

“We’ve noticed that there has to be more services for this unique population,” Harper says. “We’re still learning what they need and how to care for them best… not everyone is equipped yet to care for that particular population.”

But for SYM, any person between the ages of 13 to 26 living on the streets is exceptional and requires special care. It’s a big decision to live that way, one that is made after much pain and turmoil. Freedom of choice is important for this group, Harper says, even after they first reach out to her for help.

“Young people will come to us at one point, and maybe eight years later they’ll still be with us. We want to show youth that, you know, you will make a variety of choices: some of them will be great, and we’ll celebrate those with you. Some of those will be horrible and will set you back quite a bit, but we’re going to be here for you and help you navigate those. As long as you take the choice to try, we will be there for you.”

***

Shana awoke from her meth binge. She could feel the grime from days of not showering, the rumble in her stomach from days of not eating. The drug had lifted her far away, but now her harsh reality was resettling itself in around her.

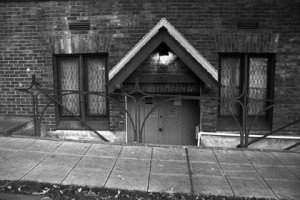

There was only one place to go. She walked up the street to a familiar pockmarked brick building; its descending concrete steps guided her to the weathered doorway. It had been a long time since she was last here, but almost instantly her appearance in the front room drew excited greetings from several familiar voices.

“Shana!”

She was enveloped in hugs from three SYM volunteers, three friends that had already seen her through so much during her time on the streets of Seattle. She could see the smiles stretched across their faces as their arms reached for her; she could feel the warmth of their happiness in her return. She felt then, more than she had ever felt before, that no matter what she did, whatever horrible decisions she made or precarious predicaments she got herself into, this would always be a place that would welcome her just as she was.

***

Street Youth Ministries began in 1993 as an overnight shelter for homeless youth in Seattle’s University District. A group of people had noticed the young bodies seeking places to rest their heads in bushes and doorways lining the neighborhood streets. Wanting to do something more than simply walk by them every day, they opened up a shelter for adolescent homeless to get some much-needed rest and support in the basement of University Presbyterian Church.

“There would be, like, 20 or 25 youth and there would just be bed mats, sleeping bags, and they would all sleep here [on the floor],” Harper reminisces in the 2,000 square-foot hall that Street Youth Ministries now runs as an evening drop-in center.

Today, the open room is crammed with board games, foosball tables, and bookshelves stacked with various paperback novels. Racks of donated clothing and three computers line one wall; in an opposite corner, a black couch set faces the TV used for weekly movie nights and the occasional videogame tournament. There is no room for sleeping bags anymore. Within a decade of SYM’s establishment, more and more agencies dedicated to serving the young homeless population sprouted in the neighborhood. SYM changed their focus to building relationships with the youth in the area, providing a caring, sympathetic community where they feel safe and where they can come for assistance in starting to get their life off of the streets.

A sign with the four days of operation and an invitation for upcoming events is posted in the center of the heavy outer door. Groups and individuals come and go from the facility, chatting with each other and the volunteers or enjoying some quiet personal time surfing the web and enjoying a book. A large makeshift wall calendar announces future trips and activities; everything from classes on résumé writing and job hunting down to cooking lessons and even trips to see the symphony at Benaroya Hall.

“It’s stuff to look forward to, something to take your mind off and think ‘you know, maybe my life could be more like this,’” Harper says, “for them to see beyond what they see every night on the Ave.”

SYM provides resources for homeless youth to move on with their lives, to find a house, find a job, and find a healthy channel to work through the effects of past emotional turmoil. The organization is big on teaching what they see as “life skills”, instilling the social and behavioral understanding that a large portion of their protégés lack. This, Harper insists, are “necessary to do life,” to survive not only as a working adult in the future, but as a citizen with a voice in society.

But at the center of her and her organization’s work is the relationship with each individual homeless youth. Special care is taken to really foster bonds with the kids that visit the drop-in center, to get to know their story and their character. Notes about interactions and the changes in each person’s life are written up so all volunteers know what to expect and how they can best help every person who walks through the door, from the familiar faces to the wary newcomers.

For the staff and volunteers at SYM, it’s about building trust and the sense of a support system that most of the youth had very little experience with while growing up, Harper says.

“We just want to know them and to make them feel known.”

***

Today when Shana wakes up she’s in a bed—her bed. Her own ceiling is above her, her own floor under her feet. This small apartment outside of Seattle is her home.

The lifestyle she had on the streets is a thing of the past. Shana doesn’t miss it. She doesn’t regret it, either. Her long term goal is to become a case manager, for homeless youth or those with mental disorders or both. She wants to be just like the people that had stuck by her for years to help her finally get off the streets and on her feet.

It hasn’t been a clean transition. She bluntly acknowledges that she has fallen into old habits every so often, has hung out with friends in her old haunts for too long, has smoked weed after deciding to quit. She drinks again now, although she strictly limits herself to one alcoholic beverage each time. Finding and keeping a good job is difficult, too, although she remains optimistic.

Shana believes that she can turn her life around, has turned her life around. She knows what she wants to be. She knows how to get there. One day, Shana declares, she’ll be back in the Emerald City—but not on the streets.

“It’s just nice to know,” she says, “that when I return to Seattle, it’ll be on much different terms.”

*false name in order to protect identity