By Delayna Sutherland

Fall 2013 Kaplan Award Winner

I am a destinationless traveler. A directionless wanderer. A keeper of secrets. A lover of dreams (the big kind). A collector of fond memories and little moments. A storyteller. A developer of ideas. A maker of wishes. A believer. I’m an explorer. I have walked amongst the modern gladiators of Rome and the present day playwrights of London. I have seen the world. I have been given endless pieces of advice (a man told me once that if I ever get lost in an Icelandic forest, I need only to stand up…a piece of information I deemed worthy enough to file away in my memory for later). And for as much of me that lie below the surface of my skin, I feel anyone who doesn’t know me would struggle to guess at the chemical composition of my soul (the same could possibly be said for those who do know me as well). Likewise, I could say the same for myself guessing about others.

* * *

My reflection stares back at me blankly from the window on the bus. We hit a pothole and I momentarily lose my seating. I regain composure and watch the Emerald City flash by on the other side of the glass and am reminded to ‘Smile More!’ by the advertisement on the door of a dentist office we speed by. The corners of my mouth instinctively turn upwards. I take notice of my fellow passengers: most are dozing off, rubbing the sleep from their eyes and breathing in the early morning as they yawn. My eyes flicker from face to face and stop abruptly when I spot the old man in the corner who’s sitting alone. He’s wearing a tattered hat with gaping holes that expose his forehead, his wiry, unkempt hair poking through. His face is worn and tired, much like weathered sand paper. The old man’s silver beard overwhelms his figure and is turning white, or maybe his white beard is turning silver, I can’t be sure. He glances about to make sure no one is paying too much attention, and it seems no one is aside from me. Once he feels the coast is clear, he coolly takes sips of a questionable amber liquid from a pickle jar he keeps in his jacket pocket. He slips it back into his pocket as his face contorts in protest to what he’s just swallowed.

* * *

I’m struck with a rather fearsome and bothersome reality: I am ignorant; blissfully ignorant and vastly unaware of the intricacy of human lives that I see unfolding before me every day. It’s overwhelming to think about really. Every morning I’m startled awake by an obnoxious alarm and wrestle with myself not to hit the snooze button so that I might have a fighting chance at punctuality. I pretend to be a barista for five minutes as I press a button on my coffee machine that brews directly into my cup. Then I sit on the bus like thousands of other commuters and wonder about the details of the lives of those sitting next to me.

* * *

I stagger onto the bus and struggle to keep my balance as it lurches forward. I discover a single empty seat and breathlessly collapse into it while absent mindedly shoving my bus pass into my pocket. I curiously begin looking about, taking note of the individuals who avoid my eye contact at all costs as if my gaze will turn them to stone. I suddenly identify with Fitzgerald’s sentiment: ‘I am within and without.’ I notice the man sitting directly across from me hasn’t opened his eyes once since I boarded and assume he fell asleep on his early-morning commute. I wonder if anyone will wake him as I study his features: his Pink Elephant Car Wash beanie is crisp and clean and still has a slight crease from being folded flat, but it’s tilted off-center and contrasts starkly with his tattered jeans and plain but distressed grey crewneck. His legs are carelessly spread about, and his backpack acts as an armrest on the seat next to him and prevents anyone from sitting there. His skin is dark and helps to camouflage that he skipped a day of shaving and his full lips are parted slightly while his head rests on the window. Headphones are secured soundly over his ears, much like the other riders, and you can subtly hear the pounding of the bass as it drums to the beat of his music. Quite startlingly, and without warning, the man raises his left hand from limply resting at his side and thrusts his balled fist into the air like Tommie Smith and John Carlos did as they stood on the podium at the 1968 Olympic Games.

* * *

If culture has taught me anything it would be the infinite power of the absence of words; the limitless possibilities of saying nothing at all. All too often we forget we have this ability to convey our thoughts, emotions, and ideas with a simple glance, folded arms, or even a fist raised in the air. However, while we may not be doing it on a conscious level, we assert the authority of the unspoken word constantly: like the black man on the bus dominating the use of expressionism via silence while reviving an iconic movement from the 1960s, or, for that matter, the woman who refused to give up her seat on the bus which fueled an entire uprising. The power of our actions is greatly underestimated, while the value of our words is naively overrated.

* * *

I’ve noticed how many girls call out “love you!” as the bus or train is pulling away from the station. It’s interesting they leave out the “I” as if to avoid committing too much while acknowledging the implication of vulnerability that follows such a revelation. And I agree the “I” really is a heavy concept.

* * *

Going hand-in-hand with the power of the unspoken word I find also the power of words unspoken. I ponder the weight of the single syllable the girls failed to mention as they fluttered away from their lovers. I begin to wonder if it bothers their significant others as much as it bothers me. For some reason, I now make it a point to say “thank you” to the bus drivers, and “goodbye” as I hang up the phone (both of which I was guilty of omitting prior to this encounter). The former often means I have to shout from the back door of the bus, which warrants strange looks from passengers that I relish in as if it’s a sort of challenge for them to join me in the resurrection of politeness.

* * *

You can see the group of men sprinting from a block away, determined but still maintaining a certain lightness. The bus driver waits as the construction workers bound onto the bus. They smell of cigarettes and chaos, and they go about divvying out change for the bus fare as they heave air deep into their lungs. The group splits up to find seats and conducts themselves much like a group of school-aged boys. Little waterfalls of dust cascade from their boots and the blinding orange glare of their construction vests has faded to a dull glow of sunset. One of the two workers sitting across from me looks genuinely concerned as he shouts to the others asking if they’ve seen The General. “I’m here, Frank!” The General sounds off from somewhere in the back of the crowded bus. The men are energizing and vivacious, full of pep and savoire faire. One of the men is doubled over laughing at something the other said, exposing that he’s missing several teeth, and has a shimmering scar interrupting the rough canvas of his face along his temple near his forehead. I imagine these men leaving home every morning: pouring themselves out of bed and into their boots like hot coffee into a mug, donning crisp jeans and t-shirts that reek of laundry detergent as their wives kiss them goodbye, sack lunch in hand, their hardhats secured to their skull like a soldier’s helmet in preparation for battle. Suddenly I find myself envying these men and their brotherhood.

* * *

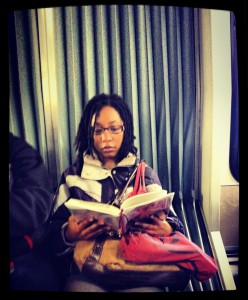

I think of all those who share my daily commute and picture the battles they face daily. I imagine the citizens of Seattle wearing hard hats every day just as the construction workers and feel this is an acceptable approach to the unexpected occurrences one might find in the urban jungle. But where is that point that, as humans, as individuals, we find common ground? When do we stop merely coexisting and start living alongside one another instead? For me, this happens on the bus. Public transportation acts as a threaded needle stitching together the fabric of our lives, seamlessly blending our differences into unexpected similarities. Together we comprise a universal culture: the culture of human experience where we can dispose of the status quo and accept that there are no rules, only exceptions. Not only am I me, but I am also the old man with the pickle jar. I am the woman who has been a nurse for thirty years and has performed a tracheotomy with a pen. I am the black man with my fist thrust in the air. I am the construction worker with the toothless grin. I am the girl who doesn’t say “I love you”. I am the bibliophile with a stack of books I can hardly carry because I like how they feel in my hands.

* * *

A few days later I see the same old man with the silver-white beard across town. He is riding a bike down the street, his whole body swaying back and forth in rhythm as he pedals, a smile plastered across his face. I can almost hear the contents of the pickle jar sloshing about in his pocket and laugh aloud at the irony.